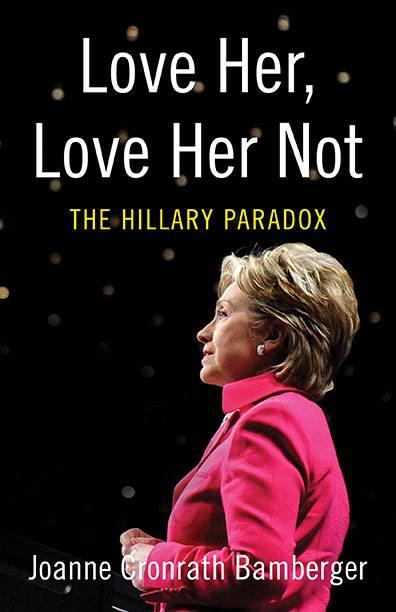

Love Her, Love Her Not: The Hillary Paradox.

So what did the book illuminate for me, other than the fact that I’m also conflicted?

Full disclosure: I supported Barack Obama in the 2008 primary. There were plenty of times I was annoyed and agitated with Hillary’s posture and demeanor toward Obama (I’m still willing to blame that on Mark Penn’s bad advice). Then again, I wasn’t happy with Obama's “you’re likable enough” comment. I celebrated Hillary’s role as Secretary of State, but got angry when I learned that during her tenure she had pushed a fracking agenda to countries overseas. It was a red flag, like her reticence to slam the XL Pipeline.

Then the email situation came up, and we were once again off with another issue to assess Hillary’s truthfulness. Yet, she dazzled me with her performance in front of the House Select Committee during her eight plus hours of testimony.

Love Her, Love Her Not: The Hillary Paradox was released on November 3, 2015, with the obvious irony that in 2016 we will all be going to the polls to choose our next President. Editor Joanne C. Bamberger (also a contributor) outlines in her foreword the motivations in digging beneath the polarity of emotions generated by Hillary. Most importantly, Bamberger wants to get to the essentials of why Hillary is repeatedly judged by benchmarks markedly different than those facing a male candidate.

Bamberger explained in response to questions I sent her, “One of the things I found during my research is that there have been several studies that show women voters must find women candidates ‘likable’ in order to see them as qualified. These essays give the larger picture about the obstacles women in general, and Hillary Clinton in particular, face, even when they are objectively well qualified for elective office.”

Essayists were chosen to represent a range of ages and backgrounds — both politically and culturally. Bamberger hopes to jumpstart a “new” conversation about Hillary. In her piece, Bamberger questions why women need Hillary to be faultless, positing that perhaps women are projecting their need for perfection onto Hillary.

So what did the book illuminate for me, other than the fact that I’m also conflicted?

It took me through a road map of opinions that fell into thematic categories, connected by the common thread of each writer elucidating where she stood on the Hillary conundrum. The obsession with Hillary’s clothes, hairstyles, and appearance intersected with reflections on ageism and sexism. There were parsings of Hillary’s pseudo-progressive bona fides, the “Bill” factor (and escapades), and some real drilldown on how Hillary can navigate her way to the White House via unapologetically clear policy initiatives. Midway through reading the book, I received an Associated Press alert that they would henceforth reference the candidate as Hillary Clinton (no Rodham), as per the campaign’s instructions.

Hmmm.

Younger women, despite their different life experiences, have clearly noticed how Hillary got slapped down in 2008 for her efforts to present herself as unambiguously equal to men. Jolie Hunsinger suggests that her Gen Y contemporaries “shake things up” and “break the molds” with a vote for Hillary.

Froma Harrop nails sexism and ageism with her observations on the insidious messages pushed on girls and women via Hollywood, outlining the narrow strictures that deem females desirable. Broadcast news and media culture also garners Harrop’s disdain (except Rachel Maddow, who is always dressed to deliver and analyze the news with authority). Additionally, Harrop points out that with baby boomers getting pushed out of jobs, the road paved to criticizing Hillary’s age (the same as Ronald Reagan when he became president) may not be a winning strategy.

I found myself falling in between the unequivocal support of Hillary outlined by Jennifer Hall Lee and Linda Lowen, and the “after all things considered” rejection of Hillary by Nancy Giles. Rebekah Kuschmider poses many of the questions I have pondered — specifically, “Why was Hillary with Bill in the first place?”

Hillary embodies the different hats that women wear. Why so much criticism from the sisterhood when one hat is exchanged one for another? When Hillary rang the doorbell to Lisen Stromberg’s suburban home and asked to use her bathroom, the incident became an opportunity for Stromberg to contemplate the reality that the aspirations of youth don’t always travel a straight line to desired expectations. Stromberg poignantly captures her feelings while describing how Betty Friedan’s book, The Second Stage, helped her to pinpoint that our society harbors a “bias against motherhood” and “doesn’t value parenting.” Rather, our culture would prefer to “fix women” than a “failed system.”

This is where the policy wonks come in, with their clearly outlined treatises on how Hillary can take the lead and direct attention to fundamental concerns faced by families.

KJ Dell’Antonia advocates for a “Put Families First Campaign.” This includes paid maternity and sick leaves, significant access to childcare, and early education programs. Veronica Arreola also wants family policy brought to the fore, but she needs Hillary to dig into her “privilege knapsack” and get real about “readjusting her view.” This means listening to the concerns of low-income women and women of color and fully comprehending their challenges. Arreola recommends that Hillary relinquish her standard platform and instead reach out to these women — respecting both their innate power and their experiential difficulties of schedule flexibility, lost workdays, and food insecurity.

American Association of University Women policy advisor, Lisa M. Maatz, delivers a 12-step manifesto telling Hillary what she can do to “earn” votes. Top takeaway: Don’t take female voters for granted. Transparency, accountability, and a multigenerational and multicultural approach are essentials. Maatz advises Hillary to “embrace” policy issues that impact women and families. Connect with the “liberal” side of your persona that will appeal to those voters who harbor longings for Sanders and Warren.

Patricia DeGennaro, a geopolitical advisor for the US Army, takes on the commander-in-chief questions, which seems to be more central than ever with the world devolving into one crisis after another. DeGennaro points to the presidency as a “male institution” — and a mindset that is ready to be challenged. DeGennaro underscores that Hillary gets the connection between global and domestic issues, and would be able to “wield both diplomatic and military power.”

My inner monologue, which fluctuates between making an idealistic choice or a pragmatic choice for a presidential candidate, was reflected in the thoughts of Lisa Solod. I loved her analysis of George McGovern as the “famously liberal, anti-Vietnam candidate who sank like a stone.” Solod reminds me of a female friend who keeps insisting, “We need someone who can win! Think of the Supreme Court!”

Right. Besides, can an openly progressive president get things done in a country that feels more and more to the right of center? I’m still waiting for Gitmo to close.

The final essay in the book, “The Long Road to Yes” by Lezlie Bishop, reveals concerns and doubts, yet also strikes a note of optimism. Bishop believes that “Hillary is the only one who understands how to work her ideological agenda within the brutal realities of global government.”

If Hillary is elected, I hope she will forge her own individual path, have Bill run the social calendar, and ultimately surprise those on the continuum — from haters to conflicted hopers — with her accomplishments.